A clean, stemline-and-stroke writing system used mainly between the 4th–6th centuries CE to carve names and short texts along stone edges in Ireland and western Britain.

Ogham (pronounced OH-um or OG-um) is an ancient Celtic writing system developed in Ireland around the 4th century CE. It uses a series of lines and notches carved along a central stemline. You'll find it most often on the edge of a standing stone or piece of wood. Each mark, or fid, represents a sound, a letter, and often a symbolic association drawn from the natural world.

Originally, ogham was used for inscriptions such as names, land boundaries, or memorials. It was carved into stone pillars across Ireland and parts of western Britain. More than 400 ogham stones still survive today, standing as some of the earliest written traces of the Irish language.

Over time, ogham grew beyond its practical use into a symbolic and spiritual system. Later medieval texts linked each letter to a sacred tree or plant, creating a poetic and mythic language of nature. Modern Druids, poets, and seekers often use ogham as a meditative tool or divinatory script, drawing on its deep connection to both language and landscape.

Today, ogham can be studied as history, practiced as art, or explored as a personal ritual language. It's like a bridge between word, symbol, and the living world.

Answer: A bit of both. In the medieval manuscript tradition (like the Auraicept na n-Éces), many of the letter names of Ogham are trees or plants. For example: beith = birch, dair = oak. But linguists argue the “every letter = tree” idea came later. Only some letters clearly map to trees; others don’t. If you’re using Ogham symbolically (as in modern Druidry), go for it, just know it’s a poetic layer, not historical gospel.

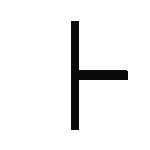

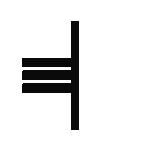

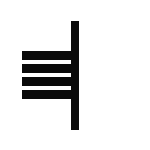

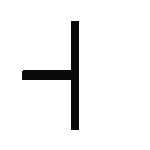

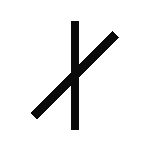

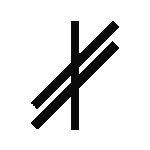

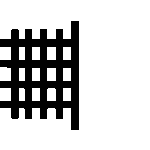

Answer: Classic Ogham stones were carved along the edge of the stone, not across the face. Today, that edge is what we’re calling the “stem line.” Most early inscriptions read from bottom to top. The letters are grouped by stroke patterns (called aicmí) that mark direction and count. If you’re designing Ogham art or digital graphics, you can keep the authentic “stem + strokes” style, or modernize it intentionally… both are valid, just pick your vibe.

Answer: Historically, Ogham stones were mostly name markers (“X son of Y”). But medieval texts like the Lebor Ogaim mention secret and gesture-based Ogham systems: finger Ogham, nose Ogham, and more, hinting that it was also used symbolically or magically. Modern Druidic and Pagan traditions use Ogham sticks (staves) or cards for divination. That’s a creative revival, not a confirmed ancient practice, and that’s okay. It’s living myth in motion.

Answer: The Ogham we see today is the descendant of several phases. The earliest “orthodox” Ogham (4th–6th centuries) was purely stone-carved. Later “scholastic” Ogham, found in medieval manuscripts, added extra letters (the forfeda) and became more symbolic and flexible. In short: early Ogham was practical writing; later Ogham was more esoteric, educational, and magical. Modern versions borrow from both worlds.

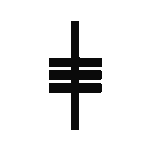

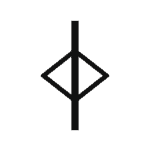

Ogham letters are organized into four primary groups, or aicme, each containing five characters. Every letter represents both a sound and a natural symbol, most often a tree. By exploring the aicme, we trace how the early Celts connected their written language to patterns in the natural and spiritual worlds.

The first aicme forms the foundation of the Ogham alphabet, representing the primal consonants and core elements of creation. These letters are among the oldest in the system, associated with beginnings, growth, and the vital relationship between language and nature. In both linguistic and symbolic use, they anchor the script in the living world… from birch’s renewal to ash’s bridge between realms.

First Aicme

Letter

Tree

Strokes

First Aicme

Letter

Tree

Strokes

First Aicme

Letter

Tree

Strokes

First Aicme

Letter

Tree

Strokes

First Aicme

Letter

Tree

Strokes

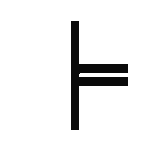

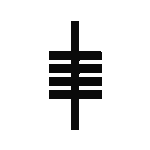

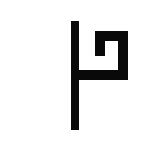

The second aicme extends the language of the Ogham into challenge and strength. Its letters carry the energies of protection, confrontation, and endurance… the trials that refine both word and spirit. In historical use, these sounds deepened the range of the script, and in symbolic tradition, they mark the passage from raw potential to tested resilience.

Second Aicme

Letter

Tree

Strokes

Second Aicme

Letter

Tree

Strokes

Second Aicme

Letter

Tree

Strokes

Second Aicme

Letter

Tree

Strokes

Second Aicme

Letter

Tree

Strokes

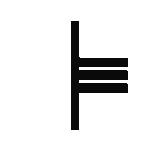

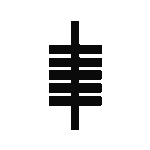

The third aicme moves into transformation, craftsmanship, and passion. These characters link the Ogham to human creation such as art, forge, and desire. Their symbolic meanings often reflect the balance between will and wisdom, the discipline of shaping something lasting from both fire and feeling.

Third Aicme

Letter

Tree

Strokes

Third Aicme

Letter

Tree

Strokes

Third Aicme

Letter

Tree

Strokes

Third Aicme

Letter

Tree

Strokes

Third Aicme

Letter

Tree

Strokes

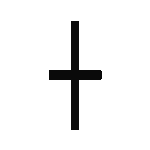

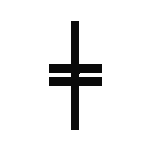

The fourth aicme completes the original Ogham set, turning toward reflection, depth, and spiritual endurance. Its letters express endings, insight, and the wisdom that follows trial. Linguistically, they represent later developments in sound and form; symbolically, they carry the quiet authority of closure and the seed of renewal.

Fourth Aicme

Letter

Tree

Strokes

Fourth Aicme

Letter

Tree

Strokes

Fourth Aicme

Letter

Tree

Strokes

Fourth Aicme

Letter

Tree

Strokes

Fourth Aicme

Letter

Tree

Strokes

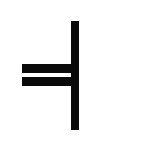

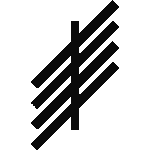

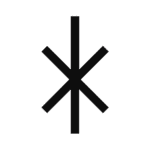

The forfeda are the five supplementary characters added to the original Ogham alphabet during the medieval period. Introduced to represent additional vowel sounds and letter combinations, they expanded the script beyond its earliest form. Over time, these symbols took on layered symbolic meanings, reflecting refinement, completion, and transformation within the Ogham’s evolving system of wisdom.

Forfeda

Letter

Tree

Strokes

Forfeda

Letter

Tree

Strokes

Forfeda

Letter

Tree

Strokes

Forfeda

Letter

Tree

Strokes

Forfeda

Letter

Tree

Strokes